TECHNOLOGY AND POWER | BIG INNOVATION CENTRE

How emerging technologies reshape economic power, governance and global competition.

When Seeing and Hearing Isn’t Believing: Deepfakes, Democracy and the AI Dilemma

Not so long ago, a video or audio clip was taken at face value. If you saw someone say something on camera, you assumed it happened. If you heard a voice on a recording, you trusted it was real. Today, that certainty is vanishing. Technology (specifically artificial intelligence) has given anyone with an internet connection the power to generate convincing lies: videos that show people doing or saying things they never did, voices that mimic leaders with chilling realism, and personalised messages that feel eerily intimate.

As political events unfold across the world, this is no longer an abstract concern. It is a direct challenge to the foundations of democratic society.

The core issue

For much of modern history, recorded sound and moving images carried an implicit assumption of authenticity. Seeing was believing. Hearing was evidence. A video or audio recording could anchor public debate because it appeared to capture reality directly.

That assumption is now dissolving.

Artificial intelligence can generate voices, faces and events that never existed, yet appear entirely real. The result is not simply misinformation but a deeper disruption: the erosion of shared reality on which democratic societies depend.

When seeing and hearing are no longer believing, the foundations of democratic trust begin to shift.

The challenge posed by deepfakes is therefore not only technological. It is political and societal — touching the core of democratic legitimacy, public trust and the ability of societies to agree on what is real.

Power implications

- Synthetic media capabilities are becoming instruments of political and geopolitical influence

- Deepfakes shift manipulation from mass persuasion to targeted psychological operations

- The erosion of shared reality weakens democratic legitimacy and social cohesion

- Trust itself is becoming a strategic vulnerability

- The ability to generate believable falsehoods is emerging as a new form of power

Beyond misinformation: the strategic nature of deepfakes

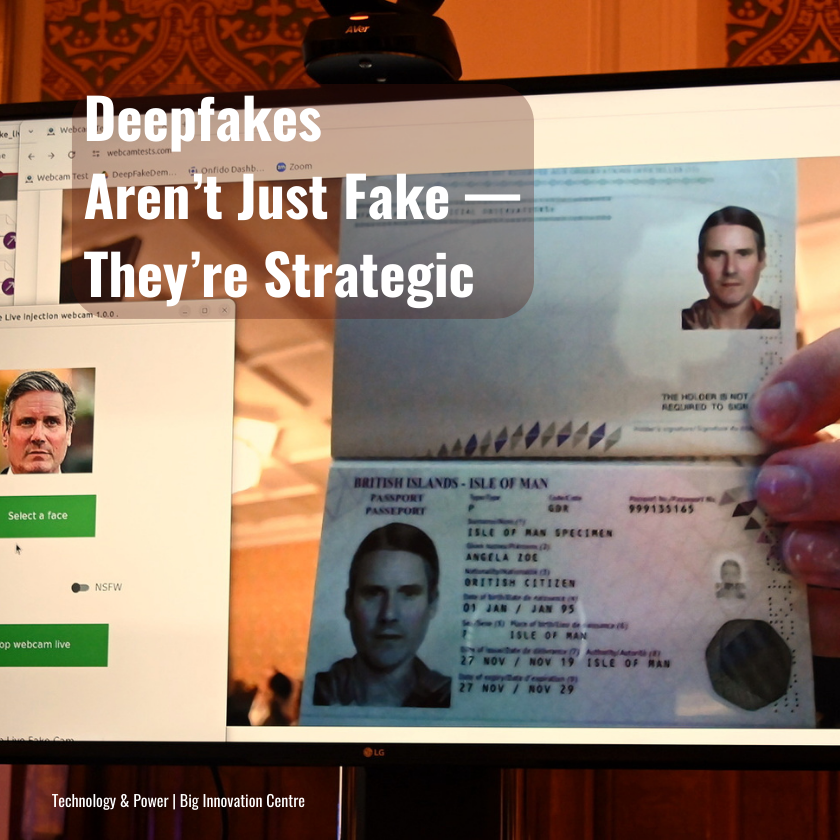

Deepfakes are often described simply as fake videos or cloned voices. In reality, they represent a broader transformation in how influence can be exercised.

Synthetic media generated by AI can convincingly mimic public figures, institutions and even personal contacts. This makes it possible not only to fabricate events but to do so in ways that feel personalised and emotionally credible. The risk is not confined to high-profile political manipulation. It extends to everyday information environments in which citizens form opinions and make decisions.

The strategic power of deepfakes lies not only in what they make people believe, but in making people doubt everything.

Once authenticity becomes uncertain, even genuine information can be dismissed as fabricated. In such an environment, the goal of malicious actors is not necessarily to persuade but to destabilise by creating confusion, amplifying existing divisions and weakening confidence in shared facts.

This marks a shift from traditional disinformation to more sophisticated influence operations that are targeted, adaptive and psychologically informed. Rather than broadcasting falsehoods widely, they exploit cognitive biases and existing beliefs, making manipulation feel plausible and personal.

It’s not just about elections – it’s about social trust

When you can no longer trust what you see or hear, the result is not a confused electorate but a fragmented one.

Deepfakes do not have to convert millions of people. They only need to influence unstable majorities, amplify grievances and erode confidence in shared reality.

That is why the danger is not mass deception so much as the weaponisation of trust. By mimicking familiar voices, behaviours and narratives, AI-generated content can create the illusion of closer relationships, making audiences more receptive to manipulation.

Once the public doubts the authenticity of what they see, all sources – even trustworthy ones – become suspect. That is a recipe not only for political polarisation but for a deeper erosion of social cohesion.

Trust itself is becoming a strategic vulnerability in the AI era.

Over time, this erosion of confidence can undermine the shared understanding that democratic systems require in order to function.

Democracy depends not only on free elections, but on a shared sense of what is real.

An escalating technological arms race

The same advances in artificial intelligence that enable deepfakes also support detection technologies. However, there is a structural asymmetry. Those creating synthetic media operate with fewer constraints, while defenders must navigate legal, ethical and technical limitations.

Detection systems are therefore often reactive, responding to new forms of synthetic content rather than preventing them. Social media platforms and digital intermediaries struggle to moderate content at scale, particularly when manipulated material is designed to evade automated filters.

In sectors such as finance or identity verification, stronger safeguards exist because incentives and regulatory frameworks align. In open information environments, however, responsibility is more diffuse. The result is an ongoing technological and institutional race in which malicious actors can exploit gaps faster than systems can adapt.

Governing in an age of synthetic reality

Addressing the deepfake challenge requires more than technical fixes. It demands coordinated responses across governance, industry and civil society.

Policymakers must recognise that deepfakes are not isolated incidents but components of broader influence strategies. Legal and regulatory frameworks should therefore address not only the creation of harmful synthetic media but also its distribution, amplification and strategic use.

Industry actors, particularly AI developers and digital platforms, must embed safeguards such as provenance tracking, watermarking and content authentication mechanisms. These measures can help establish verifiable chains of authenticity, even in a landscape where manipulation is easy.

Public awareness and institutional resilience are equally essential. Citizens, organisations and governments must develop the capacity to question and verify information without descending into pervasive scepticism. Education and transparency will play a crucial role in maintaining confidence in legitimate sources.

International cooperation will also be indispensable. Synthetic media and influence operations operate across borders, often exploiting jurisdictional gaps. Democracies and institutions must therefore coordinate responses, share best practices and establish common standards for authenticity and accountability.

The deeper challenge: preserving shared reality

Deepfakes are generated by machines, but their impact is fundamentally human. They exploit emotional responses, social networks and the fragile architecture of trust that underpins modern societies.

The real battleground is not technology but shared reality.

Safeguarding democracy in the age of artificial intelligence will require more than defending infrastructure or securing data. It will require preserving the conditions under which citizens can trust what they see, hear and collectively understand as real.

Because when seeing and hearing are no longer believing, maintaining shared reality becomes one of the central governance challenges of the AI era.

TECHNOLOGY AND POWER | BIG INNOVATION CENTRE

How emerging technologies reshape economic power, governance and global competition

Professor Birgitte Andersen is Professor of the Economics and Management of Innovation and leads research on the political economy of emerging technologies.